Albanian mob pt.2 Big Trial

The Big Trial: An Albanian-American Crime Story, from 15 Mile Road to Pearl Street

A.B.I. Crew.

Jun. 9, 2011

To understand the story of Albanian organized crime in New York City, where the murder and drug-trafficking trials of the notoriously violent Krasniqi brothers and their associates got underway this week, I had to go to Michigan.

For five hours in a prison on the Canadian border, I sat across a table from Ketjol Manoku. He’s in for murder—10 felony sentences. His latest motion had been denied the day before I arrived.

He’s 200-plus pounds and six feet tall, with a shaved head and a Viking beard. I told him he looked pretty hard. He said he used to be bigger and stronger, but he’s in pain now from an old car accident and can’t work out like he used to.

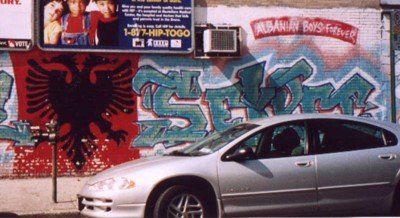

The only thing that was missing from the classic profile was a tattoo; his corrections sheet stated that he had none. But of course during the interview he pulled up his sleeve and there it was: A prison tat of the doubled-headed eagle, maybe 8 inches tall on the top part of his arm, representing Shqiptar everywhere.

30-year-old Ketjol (Keti) Manoku has been living by a soldier’s code since he was an actual soldier in the Balkans. Later, he was still a soldier, on the streets of America. For the past seven years he’s been locked up in prison, where he’ll remain on guard for the rest of his life.

He told me matter-of-factly that prison is too easy. It’s like high school. In Albania, he said, he was once beaten by police until his grey shirt was bright red and the cops were paid off the next day and he was let go. He said he fired his first gun at age 11—a Russian version of a .45.

He and his friend once saw two men get shot in front of them. One died instantly and the other was mortally wounded. Manoku’s friend reached down and took the hat off the dead man’s head and put it on his own head. “Man, give the dead man his hat back,” Manoku said he told his friend.

A lot of his friends from back home are dead now. He was a teenager in Albania in 1997 when the country went mad. There was a pyramid scheme, the country was broke, an opposition political party opened the prisons and let the inmates out. All manner of guns and munitions in the country (police, military, heavy artillery) were abandoned and free for the taking, so people took them.

One day he and his boys were sitting on some rocks hanging outside of a mechanic’s shop when a car pulled up, and some men got out. One of them brandished an A.K.-47 and said to one of Manoku’s boys: “What happened to my car?”

The A.K. was pointed at his boy’s chest; his boy stood up. It was an automatic. There were a few bursts, and Manoku’s friend was hit many times. Manoku went for the gun, the mechanic grabbed it and threw it over the fence, and the men fled. There were no arrests.

Manoku didn’t like school, and left at 16 or 17. At 19 he did a year in the army, which he described in carefully vague terms as something like special forces. He didn’t say much about the training, other than it taught him how to be good at being violent.

He went to Greece, got involved in some crime there, including counterfeiting money, and was deported back to Albania. He had five different passports.

He came to America in 2001 looking for a new life. He snuck in through Mexico, speaking no English.

HIS ALBANIAN AMERICA

He had family in Michigan (in Macomb and Oakland counties). He worked in restaurants, and lived in a ghetto area at first. He said he and his friend were once held up by two black teenagers on bikes. He saw they were shaking a bit. He and his friends grabbed the guns, and then took the bikes and tossed them. He sold the guns.

He moved on from restaurants to other jobs. He did security, helping organize concerts featuring Albanian singers in Michigan, and had a small cleaning company. He was also involved in some muscle work, persuading people to pay debts to criminals. So, say, an Albanian would be smuggled into America for a fee of $12,000; he’d pay $8,000 up front but once he’s here in America he wouldn’t want to pay the rest. Manoku would be the guy sent to convince him to settle up.

He said he broke a man’s teeth one time, and did time in county jail. He hung in the Albanian coffee shops in the Detroit area and met the infamous Krasniqi brothers there. Another Albanian gangster named Elton (Tony) Sejdaris introduced them.

He said he found out at some point that he was around Albanian confidential informants, and that the F.B.I. was onto him. He said he was in a café with the Krasniqis—the two New York-Albanian heavies whose trial has just started—when a girl claiming to be a college artist came in a few times, looking to sketch one of them for a class project. Manoku said she went to the bathroom once and he looked in her portfolio and found detailed drawings of all of them. He got rid of the pictures. She never came back again, nor did the surveillance van that had been parked outside the café those same times.

He talked about a good Albanian friend getting murdered at a Michigan concert, and about going to New York to visit the Krasniqis and checking out mobster Paul Castellano’s house. He talked about two Albanian friends who went to Chicago on a drug deal with some Latinos and were killed and had their bodies burned. He said he went there to look into it. There were no arrests.

For Manoku, there were no suits and nice haircuts and Cadillacs, like the Krasniqis favored. (A law enforcement source I talked to called the Krasniqis “gentleman gangsters.”) Manoku’s style is no style at all. No hip-hop clothes or bling: He hates that. (“They’ve seen too many movies,” he said of hip-hop-styled gangsters.) He didn’t even wear nice track suits when he was on the outside, he said. He wasn’t rich or looking to get rich.

The Krasniqis are his friends, he said. Sometimes they translated for him.

Sejdaris, who is cooperating in the New York trial and has pled guilty, is definitely not a friend. Manoku called Sejdaris a coward, and said he always thought he was the weakest link in his network. He has the same dislike and contempt for a man who took a plea deal—Florjon Carcani, eight years—and testified against him and his two co-defendants: Edmond Zoica, life sentence, and Oliger Merko, 8 life sentences, two aliases. Manoku blames Carcani for lying in exchange for leniency, and for destroying his life.

FIREFIGHT IN DETROIT

There was apparently some friction between two groups of young Albanians. It was about north versus south Albanians, or perceived disrespect, or something to do with a woman, or a physical fight, or all of the above. When I pressed for details Manoku offered a lot of “let’s leave it at that.”

Manoku said he called for a peace meeting after an altercation and hands were shook and the beef was supposedly finished.

A week later two north boys jumped his boys. Manoku said he made phone calls and the other crew didn’t yield; they basically said that was how things were going to be.

He said two nights later, on July 17, 2004, at around 11:30 p.m., he was hanging in the parking lot of an apartment complex with his friends. Manoku’s friend Merko was getting married the next day. It was the first time in his life Manoku ever had a drink; half a cup of beer to celebrate. He didn’t know it then, but soon after he’d be going to prison for the rest of his life.

Manoku said a van rolled into the parking lot with five people in it. He called out, “What’s up.”

Manoku said an A.K.-47 was pointed out the window of the vehicle. He said he went under a bush where a nine-millimeter was stashed and pulled it out and said, “Put the gun down.”

Manoku said the car accelerated toward him, and he fired, hitting four of the five young men in the van. One of the men, Marikol Jaku, 20 years old, died; the others were injured. (One of the victims injured that night, Ilirjan Dibra, pled guilty in Macomb County four years later to assault with intent to do great bodily harm.)

Prosecutors say Merko, the friend of Manoku, later tried to retrieve $2,000 and two guns and two boxes of ammo he gave to a friend. He wanted the weapons to kill witnesses, the state charged. The friend had turned in the weapons to the police the day of the shooting; Merko ended up assaulting him. Merko’s wife-to-be and family sold their house and business and fled the state; prosecutors say he told them if they talked or went to the police he’d blow up their house. (Manoku disputes this account.) Merko fled to Worcester, Mass. and then to Paterson, N.J., where United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the F.B.I. tracked him down and arrested him about seven months later.

When the verdict was read at trial, Zoica reportedly put his face in his hands for a moment. Merko and Manoku showed no emotion.

The state also charged them all with conspiracy and premeditated murder, asserting that they plotted over a period of time to kill these north boys in various scenarios: by opening fire in a coffee shop, shooting AK-47s while driving by on motorcycles, shooting them up close as they waited in traffic.

There was also an earlier incident, a federal charge, that the state used against them:

It was a fight between an Albanian I’ll call Q (a friend of the north boys who were shot in the car by Manoku) and a man named Drini Brahimllari, a friend of Manoku and his boys. Manoku and Zoica and two others of their group found Q and a friend a few days after the fight in a parking lot. Manoku told Q and the friend to get in their car. In the car Manoku pointed a gun at Q and Zoica pulled a knife on him. Zoica was getting a little crazy, threatening to kill Q. Manoku grabbed Zoica’s hand and said not to hurt him. Then Manoku’s gun went off. Q and his friend jumped out of the car and ran.

Two weeks later Q was again summoned by Manoku, this time to the parking lot of the Tirana Café. He was picked up, driven to the apartment of Brahimllari, and he followed Manoku and Merko upstairs and inside. Brahimllari and Carcani were already there. Plastic was laid on the floor, presumably to catch blood. There were 10-20 kitchen knives laid out on a table which Q was led past. He told Q to kneel. Merko brought out a gun and a pillow, he put the pillow in front of Q’s head and put the gun against it.

Merko told Brahimllari to turn up the volume on the television. Merko cursed at Q, and threatened him, and told him he had disrespected him. Q pled for his life (Merko later told Carcani he let him live because he begged). Merko said Q had two days to come up with $1,000 dollars for Brahimllari’s fight, and related medical bills. A day late and he’d be shot. They drove him back to the café.

Q told his father everything. The next day Q and his father drove to a public park and met with Brahimllari and Carcani. His father paid and asked for his son to be left alone. I reached out to Q, apologizing for invading his privacy, asking if there was anything he wanted to say, even anonymously. Q got back to me. He said he would appreciate if he wasn’t mentioned by name in any of the stories.

“I have moved on and things are going good for me,” he said. “Thank you for understanding.”

Carcani is in federal custody in Arizona with a 2014 release date. Brahimllari fled to Albania, was eventually extradited back to the States, and is currently incarcerated and awaiting deportation.

The F.B.I. agent who worked the case in Michigan called Merko the closest thing to a leader. He said if anybody put fear into the Albanian community it was Merko, who had a reputation built on having beaten an earlier attempted murder case. The agent disputed that the north boys had a gun in the car; no A.K. was ever found. He also said that Manoku had a drop on the guys in the car. He was right there, and ready for them. They didn't have much of a chance.

In an Albanian club in Detroit, I met a man who knew Jaku’s family. He said he doubted they’d talk to me, but I told them to put the word out. He said it’s a tough community to crack. Among themselves they said something about recently having seen the father of one of the men involved in the case; they said he hasn’t been the same since it happened, and that he’s devastated.

CONSEQUENCES AND CONFESSIONS

Manoku said he’s sorry he killed Jaku. He said he didn’t mean it, and that he only meant to injure the people he shot at. He said I shouldn’t contact Jaku’s family, because they’ve suffered enough. He said at the time he would have confessed to manslaughter or second degree murder. He says if you do the crime you do the time. He insists there was no conspiracy.

He plays spades and chess. He works out with two men he’s cool with (he has no friends in prison), one of them Mexican and the other African-American. He enjoys and loses himself in Adam Sandler and Ben Stiller comedies.

He’s made a point of never talking to cops, detectives, the F.B.I. or, before he talked to me, reporters. He stayed mum throughout his trial and sentencing. He pointedly wanted nothing from me and wouldn’t take anything from me in a room full of vending machines. He wouldn’t touch the Coke or the bag of Skittles I bought, just to give him something.

He read the list of the indicted people involved in the upcoming New York trial. He knows the people; he said there are people he and his associates had beef with from Michigan. He wouldn’t speak on it though.

He believes in a god, though he said he’s not really religious. He reads the Koran and the Bible.

I asked him what he would do different if he had a chance to live his life again. He paused, as if, even in his current circumstances, he’d never considered it. He said if he had to do it over again he would just own a simple house and have a small business and family, with no great plans. He said there are other crimes he regrets that he hasn’t been arrested for but he’s not going to give me or the state anything more than we already have.

There are people who are free and have successful lives in this country and elsewhere, he said, and he’s not going to betray them. He’ll be taking things to the grave. I asked him whether, if he were 70 years old and taking his last dying breath, he would tell me. He said he wouldn’t.

He rarely showed emotion, other than when he talked about snitches, the thought of whom make him very angry. On Sejdaris, for example: “He wants to be tough but at the same time he wants to be a cop.”

He seemed mildly appreciative, if not actually impressed, that I gave him (and therefore his associates) my home address, on the premise that I was coming into his home and asking to know where and how he’s living.

I asked whether he was haunted by the deaths of his friends or adversaries, or devastated by the loss of his liberty. No, he said.

Did he ever cry? He can’t cry, or even remember when he was able to. He said he wants to be able to; at all those funerals when everyone was crying, he tried, because he wanted to feel what they were feeling. He couldn’t.

But there was one time in the five hours I spent with him when I felt like he wasn’t regarding me with wary contempt. (He told me pointedly that I wasn’t worthy of making it onto his collect-call list; it’s full and he would have to bump someone he gives a damn about.) It was when he quoted back from memory a line from the first article I wrote about Albanian crime, which I printed out and sent him in hopes of lining up the interview: “There are surely many mothers and fathers crying, girlfriends and wives devastated, families wrecked…”

He saw his own mother in 2008, for the first time since he left Albania in 2001. She came and stayed with an uncle in Michigan for a while and visited him in prison. It was emotional, he said; when she saw him she cried.

So what really happened? Why? How? I pressed for details, and argued for a historical record. It’s not snitching, I said. It’s truth, and therefore worthwhile.

He said he had a subscription to Rolling Stone magazine for a year and he read every word of it. I wrote for that magazine. There was one story I did where a man broke down and spilled everything pre-trial, and another in which a man took me into his world and committed crimes in front of me. Manoku told me he appreciated reading about that sort of thing but wouldn't do it himself.

“I just don’t want to break it down,” he said.

My appeal to Ketjol Manoku was, and is, this:

I’m not looking to get you off of charges or to bury you or judge you or get my name out there by exploiting you and your life, your secrets, your misery or your gangster glamour. Don’t tell me about it; tell the Albanian community that was so shocked by the incident in 2004. Tell today’s little Keti, a 16-year-old Shqiptar who saw all those movies and sees his 1997 Albania in an American ghetto and gets disrespected one day and has to make a decision on how to be a man with honor. Tell him what the truth is, what it’s like, what he should do and not do and what may or may not happen.

I told him to send me a letter, and to tell the story in his words, so there could be no question of twisting what he says. (This is obviously a concern of his: He warned me that there would be “consequences” if I twisted his words.) He said he might. He agreed, in principle, to the idea of “shining some light” on the events of his life, and on the workings of Albanian organized crime in New York and America.

In the course of the interview, we seemed to make progress toward that idea. In the beginning, at 9 a.m., he told me there was no such thing as the Albanian mafia.

Just before 2 p.m., near the end, I was exhausted trying to convince him that what I was doing was worthwhile, driving hours of Interstate, getting messed with, stripped by, yelled at, and disrespected nastily by prison guards. (By some of them, not all.)

I told him that if I wrote what he was saying, that there’s no such thing as the Albanian mafia, even though knowledgeable readers know that there is—I wouldn’t want anyone to make the mistake of thinking he was ignorant on the topic. Was he denying the existence of the Albanian mafia because he had to, because he didn’t want to break some sort of code?

“You got the point,” he said.

I shook his hand, left him, and prepared to drive six hours down I -75 into the community he came from.

LITTLE ALBANIA IN DETROIT

When I got into the Albanian clubs down near Detroit, more than 300 miles from Manoku’s prison, I met a man who was from the same town in Albania as Manoku, and who knew him from the streets of Michigan as well. He said, “These are guys who think a gun makes them a god, and they disrespect the Albanian community.”

He said he’s seen people he’s known in Albania—normal people, “painters” and “workers”—all of a sudden turn from being people “into just a gun.” Maybe the Merkos and the Manokus aren’t actually soldiers; maybe they’ve just turned into guns.

Macomb and Oakland County are full of strip malls with fast food restaurants. It’s where many of the Albanian immigrants work. There’s 11th and Main, the downtown club area where on a Friday night at midnight community college graduates are screaming like mad about the Red Wing hockey games on the bar TVs. The girls are mini-skirted and there are bikers everywhere.

I stuck my head in a patrol car to talk to a policeman. The officer told me Detroit is too disorganized to have any gangs that last (one bust and they’re gone forever). He says the Hell’s Angels have been trying to establish a club here for years and “there’s a big element of black females riding crotch rockets,” but he doesn’t know anything about Albanians.

I went to the apartment-complex parking lot where the Manoku shooting occurred. I talked to the first two people I came across, introducing myself and apologizing for the intrusion. They were Albanian.

Of course they know about the shooting, they said; everyone knows about it. They told me about all the Albanian cafes, bars and restaurants in the area: Café Tirana, Eagle Café, Great Sport, Mocha Café, Goodfellas. (I eventually went to all of them.)

One woman who just got back from work wearing her pain clinic shirt said she was sorry, she was late, she had to pick up her boy from soccer practice. She said quickly that she thought a family affected by the shooting used to live next door but they moved.

There was a young Albanian, 14 maybe, who was already conditioned not to talk to me.

There was a young woman squatting in the square, cars going past on the service road at 45 miles an hour, cradling her infant, watching her other kids play. She said she was from Kosovo, and was willing to give me the lay of the land a little.

A black man pulled up, wearing jewelry, pulling on a Newport, asking me what’s up. He asked if it was my brother who got shot, because why else would I care so much.

A middle-aged white woman standing on her small terrace gardening told me about the schizophrenic Albanian woman across the way, and said a little woefully, “I’m kind of like a minority here.”

Three young men from El Salvador pulled up. Si, si, they know about guns and weed and ladrones. We’re nice, from a nice country, they say.

In one Albanian café a man who said he knew Manoku from Albania told me Manoku was a Gypsy—somehow not as much an Albanian as he is.

I met a 25-year-old Albanian-American with a degree from the University of Michigan who works in construction management. He allowed that some of these criminals are hard—he said he knows them—but he also said, not entirely unsympathetically, “These guys are hot-shot wannabes. It’s all adolescent fights over bitches.”

He said half the Albanians he went to high school with became rappers. One guy, he saw in a video surrounded by luxury cars. He thought this guy was broke; every time he saw him in the cafes he’d have to pay for his coffee. He found out later that one of the rappers knew someone at a car dealership and they let them use the cars as video props.

There were bars filled mostly with old Albanian men playing tile games, where the younger men would have to translate for me. At one café and they welcomed me to sit with them in a booth. I brought in my paper file filled with reporting documents, and spread out the contents. A little crowd gathered. The older men remembered Albania in 1997. A young female worker behind the bar who said she just got to America a few months ago volunteered that she’d rather be back home. She sat down and listened intently to all my stories, periodically refilling my coffee and water. She asked me, struggling with the English a little, then getting it with a little help from one of the men: “Sincere? Manoku, was he sincere?”

I talked to her at the bar later, asking her questions and wanting to ask her more, until the owner yelled at me to leave her alone. She had work to do. She accepted one of my business cards before I left. Neither she nor the boss who yelled at me would accept my money.

THE FEDS

The F.B.I. has a task force for organized Balkan crime, in Kew Gardens, Queens. The unit had been dissolved, but it was reconstituted two months ago.

There’s an Albanian double-eagle flag draped over one of the cubicles. The supervising agent, Lou DiGregorio, worked on the Italian mafia for 20 years. He told me a few times that the guys in the Albanian crime game are vicious.

DiGregorio keeps a copy of the Kanun on his desk. He called in an agent whose name he doesn’t want me to use, a man who has been working these cases for a while. This man was smart, funny, confident and street-smart.

He read my first article and said he knows every name in there, and had talked to a bunch of the defendants personally. He asked where I’d gotten some of the information from, and seemed surprised and a little disappointed that I’d been able to get it. Media gets in the way sometimes, he said; he prefers to have the element of surprise.

“You talked to Grezdas’s uncle?” he asked. Yes, I said.

“How did you find this guy?”

The public information officer sitting in on the interview cut in: he’s a reporter.

“You went into the social clubs in the Bronx, you know everything already, what can I tell you?” the agent said. A little flattery, a little mockery.

I knew what I didn’t know, though, and so did he. I found out from another F.B.I. agent, who is now in Cleveland but who worked Balkan crime in Michigan (the Manoku case, the Krasniqi kidnapping, etc.), that the New York agent I met is the best the agency has on Albanian and Balkan crime.

DiGregorio said the Balkan criminals remind him a bit of the old-school Italian Mafia, before the American-born Mafiosi who were no longer poor and hungry and desperate came of age. They’re punching above their weight, he said, factoring more than they ought to be able to in transnational crime, and in particular in the selling and transporting of illegal drugs in and out of America.

He’s right about the desperation of the Albanians, which they seem to take with them, however far they get from the homeland. The Albanians were locked away from the rest of the world during Communism; they went through a genocidal purge and an economic collapse. Their children got guns and shot at each other in the streets. They suffered from a horribly corrupt government.

Speedboats traveling the smuggling route on the Adriatic Sea lost (or dumped) so many young Albanian women trying to get to Europe or, eventually, America that they called it the River of Tears. Many of the girls who made it, hoping they would be able to bartend or wait tables for a few months, were pressed into lap dancing, and then other things.

ALBANIANS AND CRIME

I interviewed the scholar Jana Arsovska, a professor at John Jay College who used to work for Interpol and is an expert on Baltic and Albanian crime. She is working on a book about the kingpins—Acik Can, and the Dacic brothers, Hamdija and Ljutivia, Naser Kelmendi—and their huge networks and business empires; the Chinese immigrants who use Albania for smuggling; and the Kosovo Liberation Army, which produced lots of young men who know how to kill and no longer have a war to fight.

In the book, she documents huge amounts of cocaine seized in ships, and identifies godfathers of the people who inhabit the most-wanted list, with their clubs and hotels and business and government connections. Men like Princ Dobrosh, who had plastic surgery on his face and escaped from prison, and Dhimiter Harizaj, who was arrested in March on charges of involvement in international drug trafficking. The arrest followed the seizure of 200 kilograms of cocaine found mixed into a shipment of palm oil that had originated in Colombia and traveled the drug route from Colombia, Spain, Belgium, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia and Macedonia to Albania. It was the largest cocaine seizure in Albanian history.

The Krasniqis are small-time, in her estimation, as she considered the weight they moved in the indictment. And they’re not sophisticated. But she allowed that they’re all connected, the Krasniqis and the Detroit players and a recently busted operation in New Jersey.

Of course, some connections to Albanian criminal culture are more real than others.

You have the rappers—the young guns all over YouTube with the Lamborghinis and the rims, posing in parking lots in the Bronx or Yonkers or Staten Island or 15 Mile Road outside of Detroit, wearing double-eagle bandanas stick-up style, brandishing A.K.s or pretending to, smoking weed and calling out real and fake Shqiptar. There are hip-hop groups like The Bloody Alboz, TBA, Uptown Affiliates, and Unikkatil whose names ring bells with young Albanians in the streets and clubs.

Sample lyrics:

It’s the red and the black, got the warrior blood in my veins

and

I got a lotta brothas, terrorists, killaz, mafiaz, drug dealaz

And most of them soldiers, they used to be rebels, living by the mothafuckin gun, so if you

ever even think about fuckin with Albanians, I swear to god you gotta’ run

Then you have the middle- aged business men, connected and associated with Italian mafia: Alex Rudaj and his Corporation types. Rudaj is still stoic in prison, the F.B.I. says; he won’t say a word. He made his money, then was duly locked up as part of the F.B.I.’s Trojan Horse operation.

You have the middle-management, little sloppy kingpins with their diversified gang members. In 2009 two aging pilots were caught flying 10 kilos of cocaine from Florida to Ocean City Airport in exchange for $15,000. They were caught as part of a four-year-long sting investigation into Balkan criminal enterprises. At least 26 people were charged with distributing and intent to distribute heroin, cocaine, weapons, methamphetamine, ecstasy, Xanax, Oxycodone, Percocet, crystal meth, contraband cigarettes, ketamine (Special K), anabolic steroids and counterfeit sneakers.

The network was headquartered in Paterson (where Merko from Detroit fled and was arrested), and it had ties to Albania, Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia, Canada, the Netherlands, Brooklyn and Staten Island.

The suspects used the planes to import ecstasy, Oxycontin and marijuana from Canada and cocaine from Florida, authorities said. They also allegedly discussed importing Ecstasy from the Netherlands and heroin from Serbia and Turkey. The F.B.I. infiltrated and purchased over 30,000 ecstasy pills, 2.5 kilograms of heroin, a 9 mm handgun, two assault-style weapons and stolen jewelry. Wiretaps and video surveillance at the Royal Warsaw Restaurant and Bar in Elmwood Park and the Borgata Hotel, Casino and Spa in Atlantic City led to the arrests.

The ringleaders were Myfit (Mike) Dika, 44, arrested in an Albanian restaurant in Toronto; Kujtim (Timmy) Lika, 45, still at large (F.B.I.’s Most Wanted in Jersey and supposedly the cousin of the Lika who put a $400,000 hit out on a Giuliani prosecutor); and Gazmir Gjoka, 56, who was arrested in Albania. The group also included a man named Rodan Kote who surrendered to the FBI at Newark’s Liberty Airport.

This was a global operation but it was also ridiculously local. The John Jay professor said that a number of her Albanian students have indictments, charges, connections, warrants due to connections or affiliations with members of the Jersey organization.

You have the lone wolves and freelancers, who are a frightening combination of highly capable and totally unpredictable. This type is exemplified by Din Celaj. Now 27, he started a life of crime at age 10, building up to a sheet that now includes extortion, gun sales, drug sales, burglary, stealing and selling luxury cars, hostage-taking, bank fraud, insurance fraud, credit-card fraud, reckless endangerment, resisting arrest, home invasions, discharging a weapon on the Hutchison River Parkway during a car chase, and shooting out a traffic camera on a highway in the Bronx after he ran a red light.

When Celaj was 16, a bouncer refused to let him into Scores, the strip club. He called some friends, who stopped traffic on the Queensboro Bridge while Celaj leaned across the railing with an Uzi and put six bullets through the windows. In 2009 he recruited an active duty New York City police officer, Darren Moonanto, to help him rob drug dealers.

And you have the 17-year-old Albanian boys in the city, many of whom feel isolated and alienated. They’re prime recruits for the criminal life.

One teenager I know of is in a transfer school (for students who messed up, or are messing up, in school). He’s the only white kid there. Maybe he’ll join a gang or something like it; maybe not a crew with a name but just a bunch of friends who run together, and there will be a dispute about a girl, or a debt will be owed, or he’ll meet somebody who’s connected, and he’ll run across an opportunity to earn a living without taking work in a fast-food restaurant, and he’ll take it.

THE SPECIAL CASE OF ALBANIA

I’ve gone into seemingly every Balkan bar, café, bakery, and social club in the Bronx and Queens, Staten Island and Detroit. I sent a letter to an Albanian man who was being extorted by two Albanians, who came to his front door with guns, threatening to rape his wife. Both were Krasniqi soldiers. The man shot one dead and injured the other (whose brother is most wanted by the FBI). I’ve called so many disconnected numbers, seen so many Balkan aliases, misspelled and differently spelled names and social security numbers linked to multiple people. I’ve been threatened with violence. I’ve been thrown out and hung up on. I’ve been told many times, usually after I started asking questions, that the club I’m in is “private.” And of course I’ve been ignored.

I’ve been asked why I care about Albanians; repeatedly, I’ve had beefy guys ask me “who gives a fuck about the Balkans.”

I’ve talked to a tatted up, patched up, vested up Albanian biker at 3 a.m. while he was hanging with twenty other bikers on a curb in Queens. His cousin turns out to be one of the men under indictment in the upcoming NY trial. He’s from the Bronx and has the Albanian Eagle patch on his vest not far from his RIP patch. He was good enough to talk to me, unlike the boy in the bar who was too scared or cocky to admit he’s an Albanian, then ignored me; his partner told me I’d better get out of there, and laughed. (When I asked him what was so funny, he didn’t answer.)

At that same club, the Albanian hostess said she was willing to help me out. I gave her all my cards and she said she’d spread the word that I was doing a piece. I’ve been thanked by a young Albanian for what I’m doing and have been told by a middle-aged Albanian that I’ll be rewarded for all this running around in prisons, streets, clubs and housing complexes, somehow.

I met the kindest sweetest old man, an Albanian shop owner in the Bronx named Gjin Noku, who sells VCR tapes that nobody comes in to buy anymore. The man sat me down in his chair and patiently told me all about Albanian history and politics and culture. He said he’d talk to me about anything, and said I could use his name, he didn’t care. He told me about everything he’s heard and seen, and about the young Albanian criminals. “They’ve suffered and they want to become rich in one day,” he said. He told me about the $20,000 it now takes to legally immigrate to America, and said that America is too poor to come to now, anyway.

Noku said his wife was disabled from 9/11 cleanup, and that his son has somehow gotten caught up in crime. He was an innocent young boy, Noku said; a doorman and a student at Fordham. The son, Spartak Noku, was arrested—something to do with Ecstasy. The father said he wrote to Michael Bloomberg to help clear the son’s record, but didn’t get a response. He asked me for help, and said his boy is innocent. Now Spartak is depressed and wants to do accounting work but this record comes up and he’s not allowed. He gave me an Albanian flag, a beautiful Pristina snow globe, and a statue of the anti-Ottoman warrior-hero George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, who every Albanian knows.

He wouldn’t take my money.

THE CONFIDENTIAL INFORMANT

Before the shopkeeper there was an anonymous tipster who sent me a message with names of unarrested criminals. And after that I met an Albanian criminal who said he’s the owner of six cafes and has been arrested six times.

The criminal has a bullet wound and carries a money clip with 100 dollar bills. After a while of back and forth—I can’t tell you that, I shouldn’t be telling you that—he decided to tell me that he’s working for the F.B.I. as a confidential informant. He showed me his F.B.I. agent’s card (he referred to the officer as both an agent and his lawyer). The information he gave me seemed plausible but relates to events that are ongoing or have yet to be confirmed by law enforcement. (I subsequently ran what I could by the F.B.I.; their response should be forthcoming, despite the fact that they expressed surprise and disappointment that a C.I. introduced himself to me as such.)

I knew it was possible the C.I. was lying to me. I didn’t assume the F.B.I. wouldn’t lie to me either; I asked the agents if they would lie to me to preserve an investigation, and the supervisor said no.

I’ve been lied to on this story before over the simplest of things. A 50-something owner of a restaurant in Detroit said he didn’t know any Albanians anywhere in the area, and never heard or saw anything related to Albanians; an hour later I found out his restaurant was across the street from where Manoku shot up the car. The first people I ran into in the nearby housing complex were Albanian, and I found six Albanian cafés and clubs within a two-block radius.

The C.I., a gregarious, back-slapping goodfella, told me that he helped set up one of the meetings between the Gambinos and the Alex Rudaj operation. He mentioned two cafés: Tony’s and Shelia’s. He told me that in an act of violence and disrespect, Rudaj stripped Joe Gambino and maybe some of his men naked. Albanians aren’t scared of an Italian mafioso, he said. They’re only scared of another Albanian, maybe.

He said he’s not scared of anything either, except one thing: He’s scared for his child’s health. He touched the Christian symbol hanging from his rearview mirror. He drove me back to his home in the suburbs; later, he’d take me back into the city. He said he didn’t want to be seen talking to me at his café, because someone might think I was F.B.I. He took photos of my ID cards with his phone.

He talked as we drove down the highway and he worked his phone. He knows Gjovalin Berisha, a defendant in the upcoming trial, who he says owned a café down the block from a café I’d been at earlier. He says the man is the nicest of guys; no violence, but heavily into drug distribution. I checked court documents later and found he was caught with 10 pounds of marijuana, and pled guilty. (The police also found in his place drug ledgers, a .380-caliber handgun, and full-metal-jacket bullets, but Berisha says they weren’t really his, the gun didn’t work, he just kind of had them.)

The C.I. also told me that the owner of a bar I had been in earlier was a major drug dealer, and that his brother is a driver for a minister in Albania.

He gave me two names that seemed to check out: Gjelosh Krasniqi and Ened or Edward Gjelaj. One is in prison in Albania for war crimes; the other, an associate of the Genovese crime family, was in federal custody and now is in a New York prison. The C.I. had them doing way more than they’re in prison for, and named two of their crime partners who are still free.

The C.I. said he’d set up traps, essentially: Cafés and bars with illegal gambling operations, to which he’d invite known gangsters, criminals and criminal aspirants. He’d make the places feel like mob clubs, and they’d all be wired by law enforcement. Some C.I.s get money for this, and some get breaks on their own crimes. Some get both.

He said the drugs usually came from Arizona, Canada and California to the Bronx, and were then sold in bars and clubs in Astoria, where there are lots of establishments run by immigrants from the former Yugoslavia, as well as Greece and Italy. He said they’re careful to keep the drugs in the Bronx and the cash in Astoria so if they’re busted they won’t get busted with both.

He said a large bust was coming soon in New York, of up to 50 people, Albanians and Italians.

I asked him if he could live his life over again what he would do. He didn’t miss a beat: he would be an F.B.I. agent. He loves the agency.

A NEW YORK STORY

There was a fairly popular Albanian singer named Anita Bitri who had her first hit when she was 16, and who came to the United States in 1996 to make music here. She lived on Staten Island. In 2004, in a tragic accident, she, her mother and her small daughter died from carbon monoxide poisoning. At the time, Anita happened to be dating an Albanian man by the name of Parid Gjoka.

Gjoka wants to write a book about it, and other parts of his life. He’s already written 375 pages.

Gjoka himself is already famous, in a way. He’s not on any of the scores of databases a reporter might check to find out about him. But one aspect he’ll cover in his book is that for years he’s been the most criminally active Albanian felon there is.

Gjoka, 33, came to the United States when he was 17 on a 3-to-6-month temporary visa with no intention of returning to Albania. He said he came for a better life. He did some construction work, valet parking and roofing and hung out in Albanian coffee shops in Ridgewood, Queens. That's where he met Kujitim Konci, a homeboy from Tirana, who he said had a reputation as one of the biggest gangsters in Albania. Gjoka wanted that lifestyle. From 2000 until his last arrest in 2008 all he did, everyday he said, is commit crimes.

He’d drive to Michigan to pick up 40 to 50 pounds of weed from Canada and he’d take it back to New York City, Konci tailing him in case he got pulled over. (The emergency plan was for Konci to smash into the police car and say he fell asleep at the wheel.) He said he was trafficking 50 to 100 pounds of marijuana every 10 days. He’d meet a female contact in rest stops near Buffalo and Syracuse, get into her back seat and drop thousands of dollars in a compartment, and she’d drive it across the border to pay the suppliers in Canada. He’d sit in dark cars, negotiating drug deals worth more than $100,000, sometimes with people he’d robbed in the past. These guys would demand to see each other's families and to be shown where they lived before they did business together, so they’d have leverage.

Gjoka had a crew, and the Krasniqis had a crew, and the two of them worked together obtaining and distributing hundreds of pounds of marijuana from Canada. In 2005 a fight broke out between the crews in a bar. Someone pulled a knife on Gjoka. Gjoka didn’t man up and fight back. (Crushed by the death of Anita the year before, he was battling a heavy coke habit.) Later that year, the Krasniqis refused to pay for a shipment of marijuana they got from Gjoka. Gjoka and his crew member Plaurent Cela went to discuss this with the Krasniqis. Saimir (Sammy) Krasniqi pulled a gun.

The Krasniqis don’t play. They sensed weakness and they were going to take over. They started causing mayhem at Gjoka crew hangouts. A war was on.

The Gjoka crew, which included Erion Shehu, Skender Cakoni, Cela, Gentian Cara and a man named Visi, strapped for combat.

The Krasniqi crew did the same. They kidnapped and beat a Gjoka crew member named Tani, Gjoka’s No. 2. Tani falsely agreed to become a double agent and spy on and set up Gjoka. Later Tani set up Gjoka by recording the two of them talking drugs and crime and is now cooperating with the government.

The Krasniqi crew killed Shehu. The Gjoka crew, on the hunt, spotted Bruno Krasniqi walking out of a bar in Astoria, Queens.

According to the prosecutor, Gjoka aimed his handgun, Cela aimed his Uzi and Cakoni had a shotgun and was screaming “Shoot! Shoot!” but Gjoka lost his nerve. Cela lost his respect for Gjoka. One member of Gjoka’s crew switched his allegiance to Krasniqi. Cela went back to Albania and attended Shehu’s funeral, but then in Albania he became tight with one of Shehu’s killers, a leading Krasniqi crew member.

The Krasniqis won. They’d pretty much cornered the weed business. Two members of the Krasniqi crew went back to Albania. One was Almir Rrapo, the civil servant to an Albanian minister. Another was Gentian Kasa, who was later shot to death in Brooklyn in 2007, one of the two soldiers who showed up on that doorstep threatening to rape someone's wife.

A Gjoka crew member, Skender Cakoni, would accumulate charges for possession of 52 grams of coke and another 40 grams hidden in his refrigerator. At the time of his arrest he was found with digital scales, grinders, a bottle of Inosital (a narcotics dilutant), Ziploc bags, a switchblade, a stun gun, a pistol, a BB gun and two Motorola “Talkabout” radios. Cakoni has also been charged as a supplier of Arizona weed (the C.I. told me that’s the cheapest product) to Gjoka. He had 200 pounds ready to sell in New York in 2007 and he once lent Gjoka his car to pick up a large quantity of weed in Detroit. They used to transport it in large hockey bags.

Muscled out of the weed game, Gjoka and others branched out into alien smuggling and ecstasy distribution, in addition to straight-up stealing.

Gjoka and his boys burglarized a Jersey catering hall for $64,000. They broke into their Queens landlord’s apartment looking for a large amount of cash they thought was there. They got a tip (from a man by the name of Hasan) that a couple who owned a jewelry business had valuables in their house; they broke in and stole jewelry they pawned for $3,000.

After they got another tip (from Angelo) that there was a home in Yonkers to hit, they made off with $7,000 in cash, two watches and a pencil gun. (It’s a gun shaped like a pencil that fires real bullets.) Angelo tipped them again that a drug dealer in Yonkers would be away, with possibly $2 million in cash and ecstasy in the place; they got as far as lacing raw meat with poison and sedatives to knock out the vicious guard dogs, but cops came by and they had to abort. They hit another drug dealer’s home on Bronx River Road but only came away with a stolen gun.

Gjoka estimates he was involved in a total of 40 to 50 burglaries.

Then there was an arson request for a factory in Jersey by a man named Louie, followed by two other arson jobs.

Gjoka and a man named Gentian Nikolli checked out a location in Vermont, by the Canadian border. On three occasions they tried to smuggle aliens: four Asians, ending in failure; a restaurant owner of indeterminate nationality, ending in success; and a Croat, ending in the Croat’s arrest. In 2007, Nikolli himself was arrested by federal agents, caught in the act of alien smuggling.

Gjoka also admitted to supplying the money for one of his boys to move cocaine from Colombia to Albania. He had another plan to move four kilos of heroin from Florida. He used his Queens apartment as a stash house for the cocaine.

He was arrested for a gun charge in 2004, for a D.W.I. in 2005, by immigration in 2007 and for a bar fight in 2008. Just before he was about to be deported the F.B.I. arrested him in this case. He signed a cooperation agreement with the government in 2009. I heard a defense lawyer say that Gjoka will have spent $180,000 on him, and that he'll wind up getting a new name, a new identity, and a spot in a special witness-protection program.

These events are all true, as Gjoka now testifies. But he was forced by prosecutors to go through his draft of the book, line by line, to separate fact from fiction. Gjoka had copped to, to him, what must have seemed like the pettiest violation of all: At the suggestion of one of his criminal associates, he lied about some of the events in the book to make it more sellable. Now it's not petty at all.

THE TRIAL

The first New York Albanian-mob trial started this week, in a federal courthouse on Pearl Street in Lower Manhattan. Originally there were nine to 11 defendants; Six have since pled guilty, including Daniel Bertram Weis (a.k.a. Daniel Weiss, a.k.a. Berti, a.k.a., variously, Albert Tamali, Temali, and Tamoli), a 7th-grade dropout from Michigan, who was part of a weed-distribution operation trafficking from Detroit to the Bronx. Also pleading was Gentian Nikolli, 34, who came from Albania when he was 21, had guns and access to fraudulent documents, talked of robbing an armored car, and, prosecutors said, had a reputation in the community for stabbing, punching, kicking people in the face, and committing other acts of violence a “remarkable” number of times. (He assaulted his own father.) Someone who owns a bar in Ridgewood posted his bail.

On May 13, 2011, the U.S. Attorney requested that a plea deal for the Albanian civil servant, Almir Rrapo, be unsealed. On June 6 I asked the clerk for it and was told that the judge’s staff hadn’t yet sent in permission for the plea to be public. I put in the request and that night received the document.

The 28-year-old Rrapo, holder of a Masters degree in political science, pled guilty to nine felony counts and agreed to provide assistance to the U.S. government. He said that from 2003 to 2010 in Manhattan, Queens, Detroit and elsewhere, he was part of an operation that distributed 100 kilograms of marijuana (street value $3 million), robbed a marijuana dealer, kidnapped a rival drug dealer, conspired to murder a marijuana supplier, murdered Erion (Lonka) Shehu. Rrapo also copped to possession of ecstasy with intent to distribute, and to supplying guns to others, including one with a silencer.

He’ll be sentenced on July 11.

On the first day of trial, Gentian Cara, from Toronto, had his case severed. (He’ll be tried later with the Krasniqis, have his own trial, or plead out). The government has 35 hours of audio recordings in Albanian in this case, 99 minutes of video evidence, and 9,000 pages of telephone-pen register records. Cara argued that evidence on some of those recordings will help his case. The interpreter said she’s already listened to about 100 telephone conversations (most in English) but there are 13 telephone calls in Albanian. The interpreter told the judge she’s still working on the first call.

A D.E.A. agent took the stand and broke down the weed game in New York City: low-grade commercial outdoor-grown weed from Mexico (mashed tight, wrapped in industrial Saran Wrap, sprayed with an odor-masking chemical, wrapped again, boxed and shipped), $500 per pound, wholesale; Arizona weed (also grown in Mexico, called Ari or Zone), $1,000 per pound; Jamaican Yard weed, $1,500 per pound; hydroponic or boutique weed (usually grown in the northwest United States, northern California or British Columbia: B C. Bud, never mashed tight, heat-sealed or vacuum-packed fresh, sold wholesale for $4,000 to $6,000 per pound, with a street value of $14,000).

Plaurent Cela and Skender Cakoni are now the only ones left in the the first trial.

Cakoni seemed to be the harder of the two. The D.E.A. raided his Bronx apartment nine years ago. He was an enforcer, dealer and lieutenant to Gjoka, who was looking to go higher and deal directly with the Canadian connection, but never got to give up his job working in a city pizza shop. When everyone stood in the courtroom for the judge entering and exiting he was the only one who stood with his hands behind his back, as if he’s naturally always ready to be cuffed. He seems a bit like classic yard material; greased-back hair, yakking and arguing with his lawyer, a bit weathered, too skinny and streety for his suit or any suit he’ll ever wear.

Cela, 29, seemed like a kid and smiled a few times, and blew a kiss at his broken-English-speaking parents. They mouthed Albanian words to each other. They sat a seat away in the gallery, next to me. (We were the only people there.) Cela’s parents, the mother especially, seemed tense and worried sick about their son. They talked to me. They’re spending their life savings on him and think he’s innocent; the mother almost cried while she was telling me this. They told me their life story, their son’s life story, but they said they really shouldn't say anything while all this is still going on, so I won’t provide details yet. Upsettingly, given how much they were paying their son's defense attorneys, they have no idea what’s going on with their son’s trial. I explained the role the jury plays, the role the judge plays, what could happen in terms of verdict, sentencing, what voir dire was, about all the sidebars. The mother kept on running up to her son's lawyer, who eventually told her to sit down and let him do his job.

When Gjoka testified, he got into detail about the death of the singer Anita, details he wasn’t even asked about. He called her his “soul mate.” Her death was his downfall. He said he loved her like he did no other girl. He was the one who found the dead bodies. After her death he said he wanted to kill himself many times. He did drugs heavily to try to forget. He had some sort of “spiritual visions” about her. He said the grief almost made him “lose his mind.”

After Gjoka’s testimony a few of the defense attorneys gathered around, smiling and laughing. They mocked Gjoka’s “spiritual visions,” what he'd said about the death of his soul mate.

As someone who watched his own soul mate die a horrible death—the girl, my wife, died in my arms, and I put her in the body bag—I actually understood what Gjoka was saying, and felt like he was being completely, painfully sincere in what he said on the stand on that score. I knew what he had been through. Presumably, those lawyers didn't. Or they just didn't care.

EPILOGUE

Two men connected to the case are still at large: Dukajin (Duke) Nikollaj and Visi (last name unknown). The Canadian kidnappers, assaulters and drug suppliers are still free.

A tip I got from an anonymous source said one of the Krasniqis had been kidnapped and beaten in Michigan by two men who lived in Canada and entered the U.S. illegally through the trucks they were using to smuggle in their marijuana and Ecstasy. The two names he gave me do seem to be a possibility; past addresses and related surnames match up. He said one of the men’s fathers and a father-in-law were helping with distribution and organization. He said one of the men was arrested in Canada, brought to the U.S. and is now free in Albania. That man has an old Michigan (Albanian area) address with a bad phone number and the person who lives at the address there now told me never to call there again, and hung up.

The tipster also mentioned a “big-time Mafioso” responsible for multiple killings in France, Canada and the U.S., who was arrested in Chicago in 2008 and let go eight months later. He mentioned this man’s contact was a mobbed-up Michigan restaurant owner, Italian, whom I called and left several messages for but who didn’t get back to me. He mentioned another two Albanians out of Chicago (trafficking 600 pounds of marijuana a week for 10 years, he said), and another Albanian who before 9/11 was bringing kilos of heroin into the U.S. and kilos of cocaine from the U.S. to Europe. (A man with that same name he gave me was wounded in a shooting in Albania in 2007 in a gambling dispute.)

"What you got is just kids,” the tipster told me. “The real gangsters never get caught … the FBI knows it all, they have cut deals with these people and let them work and commit crimes as long as they give somebody from time to time, that’s the way it works… I have just lost faith in the American justice system. They catch the small fish and the big ones are out while everyone knows who they are.”